Greenfield defense: Catch & kill

Last month, we explored the dramatic rise in the development of greenfield quarries nationwide, and we addressed how disruptive these can be. These new entrants adversely affect not only aggregates in their target markets but, as producers and consumers respond, also inflict collateral damage on ready-mix, asphalt, and other markets.

With stakes this high, one would expect incumbents would be proactive in aggressively mitigating greenfield threats. This expectation would be wrong. Almost without exception, the industry’s historical approach has been to ignore these threats until forced not to.

Why? Three reasons:

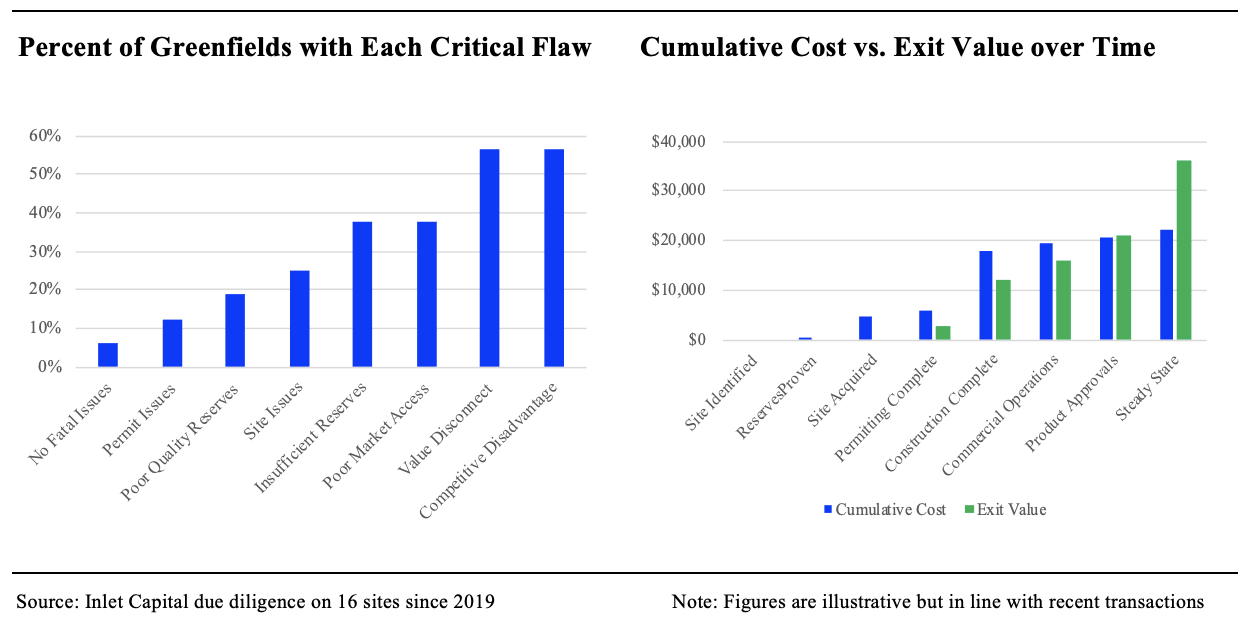

- Unsuitable sites. Let’s face it, most greenfield opportunities that make the rounds aren’t really opportunities at all. Many are deeply flawed, often with one or more insurmountable issues related to market access, reserves, permit considerations, or landowner expectations, among others.

- High barriers to entry. Greenfield quarry development is hard. It’s costly and time consuming, requiring expertise in markets, geology, permitting, construction, and commercial operations. And there’s traditionally been a disconnect between the value of the site at each development milestone and the capital required to reach that milestone. That disconnect often persists until commercial operations approach steady state, and until recently, outside capital to support new quarries has been extremely limited.

- Development disincentives. Being forced to achieve stable commercial operations before making a profitable exit is a strong disincentive to quarry development. Incumbents have been loath to provide newcomers with earlier and easier exit opportunities, rightly fearing that doing so would encourage even more development.

Fifteen of the sixteen proposed mines reviewed for analysis had at least one fatal flaw, with each site having an average of three. Only one of these mines should have had a realistic chance of advancing beyond the drawing board. But six of these sites are now operating, under construction, or in advanced development. So what’s changed?

As noted last month, high multiples, strong margins, and continued consolidation have created powerful incentives for greenfield quarry development. Debt and equity capital has become both inexpensive and widely available, and increasingly, there is on-demand expertise available that can navigate the complexities of permitting, development, startup, and operations.

The result is a cottage industry of emergent amateur quarry developers. Only two of the sixteen proposed mines referenced above were initiated by established industry producers. The rest were landowners, private developers, financial sponsors, employees-turned-entrepreneurs, and backward-integration plays. Most had visions of quick and lucrative exits, but many failed to recognize the flaws in their own sites. Whether these flawed new builds ever become profitable or not, they still have the potential to disrupt markets. And it’s no longer a question of “if” these quarries will get developed, but when and by whom.

So what can quarry operators do to defend against these rising greenfield threats?

There are a host of options available to incumbent producers, each having advantages and drawbacks, and each best suited for specific circumstances. One such option, commonly known as “catch & kill,” has been employed successfully by the automotive, energy and tech industries for decades.

In its simplest terms, catch & kill involves acquiring a threat and shelving it. In the aggregates sector, a producer could acquire a greenfield threat, ideally early in the development process, and then sit on it. Utilizing this tactic, an incumbent producer can defend its markets, preserve margins, extend reserve life, and position for future growth, all with relatively minimal capital outlay.

Catch & kill has its drawbacks. It’s a somewhat inefficient use of capital; it has the potential to reduce barriers to entry, and it can give developers an incentive to advance even more quarry sites. But in the right situation, this can be the optimal course of action.

Ideally, a solution that creates value for all parties will make itself apparent in every situation. But in reality, incumbents may find themselves having to choose between the lesser of two evils. What is right for those operators will depend on their particular circumstances. But one thing is clear, the greenfield boom is already happening, whether they have a strategy in place for it or not.

About the author:

Gregory Dayko is founder of Inlet Capital Group and is responsible for its M&A and strategy consulting practices. He can be reached at gdayko@inletcapitalgroup.com or 561-529-5569.

Gregory Dayko is founder of Inlet Capital Group and is responsible for its M&A and strategy consulting practices. He can be reached at gdayko@inletcapitalgroup.com or 561-529-5569.